POMR

Turn in your completed Medical Record at each submission deadline.

As will be expected in the veterinary teaching hospitals at WSU, your Medical Record should be clear, complete, organized and free of extraneous pieces of paper. Ideally, the reader should be able to review your Medical Record and retrospectively follow your thought processes as you worked through the case. The record should also provide an accurate legal record of the case.

The POMR is based on a Problem Oriented Approach.

- Collection of information that becomes the “data base”, including history, physical exam, and laboratory data

- Identification of the problems and differential diagnoses for each problem

- Formulation of a diagnostic and/or therapeutic plan

- Assessment (interpretation) and follow up

The components of a POMR include:

Updated Master Problem List – Update your MPL after each submission and it is always kept at the front of the record.

Data Base (e.g. lab results, history, physical exam findings, signalment, etc.)

SOAPs (including Assessment, Differential Diagnoses, Plan, and summary SOAP). The SOAP is very important. It should be updated and turned in at each submission deadline as an integral part of your Medical Record.

The concept of a Problem List is the single most important component of a POMR.

Remember, an active problem is an “abnormality”. According to L. Weed, it is “anything that may require health care management, and that has or could significantly affect the well-being of a patient” (or herd).

A problem may be:

- a clinical abnormality (e.g. vomiting)

- a physical exam finding (e.g. lymphadenopathy)

- a abnormal laboratory value (e.g. hypercalcemia)

- a disease state (e.g. diabetes mellitus)

By the time you get to your clinical rotations, you will be expected to be able to consistently generate good Problem Lists with major Differential Diagnoses early in your work-ups.

The Master Problem List (MPL) should be kept at the front of your medical record at all times – there it serves as an index.

The MPL should be updated as the case proceeds

(i.e. after receiving EACH new piece of information.)

Ideally, the most diagnostically useful, or “High Yield” problems are listed first.

“High yield problems tend to be those that point to disease in a specific organ or system. Chronic vomiting is a high yield problem: it is often seen with diseases affecting the gastrointestinal tract. Anorexia and lethargy are low yield problems: these signs can be observed in patients with disease in virtually any system.”

Problems are defined at the highest level of their understanding using all the information currently at hand.

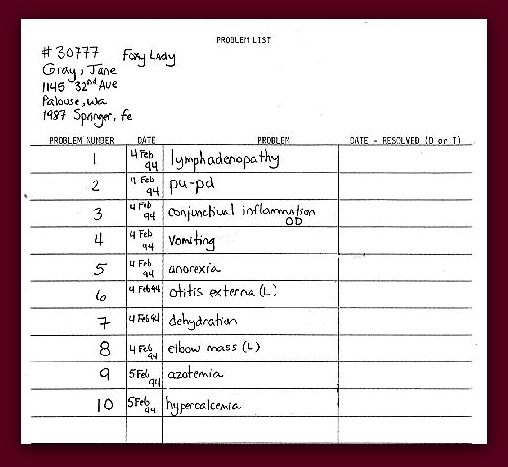

Example of an initial problem list: (courtesy of CR Dhein)

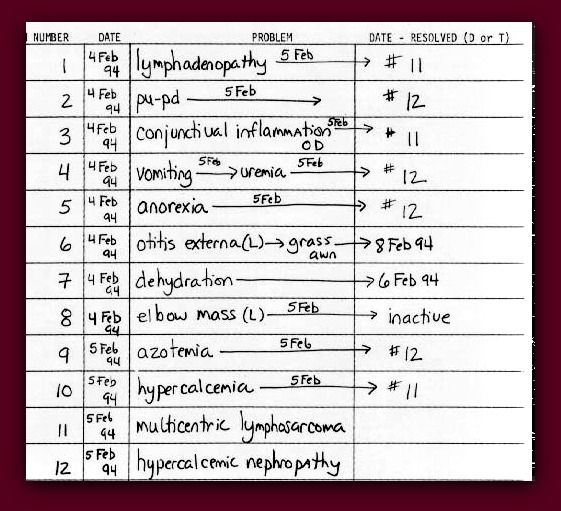

Problems can change over time and may be either:

- Resolved – spontaneously or due to your treatment

- Re-defined – to a higher level of understanding (e.g. polyuria is updated to hypercalcemia due to lymphosarcoma)

- Re-defined by combination with other problems caused by the same underlying disease

- Inactivated when no further diagnostic or therapeutic action is required

- Remain unchanged (i.e. left open)

Example of an updated Problem List: (CR Dhein)

Your SOAP should be updated every submission period.

For the Diagnostic Challenges, you should SOAP your case according to the following instructions. It is very important that your medical record accurately and completely reflects your thought processes at each step of the case.

Also, you should use the PLAN section to clearly indicate to the DC facilitator any and all procedures you want done (both diagnostic and therapeutic). Be very specific so that your facilitator can respond appropriately.

S- Subjective

Subjective evaluation of the animal’s progress. How is its mental attitude, appetite and activity? Is it improving, getting worse, or remaining the same? This section may also include similar information that is provided by the client.

O- Objective

This section should provide summaries of the objective (measurable) clinical information such as temperature, laboratory data, radiography, etc. Many clinics will use a flow sheet to facilitate assessment of serial laboratory data obtained from patients.

A- Assessment

- This may be the most important part of your record and should consist of an analysis of the subjective and objective data at this point in time. It should reflect your interpretation of the findings of the case, including how you are bringing the case together and changes in your understanding of the animal’s problems.

- Focus on “high yield” problems. (In your POMR, you should “SOAP” each of these high yield problems individually.)

- For each high yield problem, think initially in terms of mechanisms and broad hypotheses. For example, what kind of processes could cause hepatomegaly?

- You should list and address specific Differential Diagnoses.

- At the end of the case, the reader should be able to review this section of your POMR and retrospectively follow your thought processes as you worked through the case.

P- Plan

- The “Plan” section is split into two parts: Diagnostic and Therapeutic.

- The diagnostic and/or therapeutic plan should be devised based on the subjective and objective observations and your assessment of those observations.

- Indicate here the ACTIONS that you are undertaking as veterinarians on the case.

- Be very specific – especially for the purposes of the Challenges.

- Remember that the DC facilitator must respond to your actions and requests. If your plan is incomplete or unclear, you may not get the information you requested.

Your Plan should be used to:

- 1. Indicate any Treatment that you will be performing as part of your therapeutic plan. Be sure to include route, dosage, and specific drug name.

- e.g. Amoxicillin 100 mg per OS, BID o

- 2. Indicate any Laboratory Tests that are being submitted or run in-house.

- e.g. e.g. CBC o, Panel o, Urinalysis o

- 3. Indicate any Procedures that your client has approved.

- Procedures should always include a description of exactly what you want to do. Be very specific when you propose a procedure and indicate exactly what it is you are looking for, especially if you are looking for particular changes. This allows your facilitator to provide the appropriate results and to appreciate that you understand the technique.

- e.g. Thoracic radiographs (VD & lateral) o

- 4. Indicate plans for communicating with the client and document what interactions have occurred. For legal reasons, documentation of client communication may be important later.

- e.g. Communicate risks of general anesthesia to client o

NOTE: Be sure to draw a box o next to each item on your plan. Your case facilitator will mark off the box with an “X” when they provide results and that part of the plan has been accomplished. This will also help ensure that nothing is overlooked.

When your medical record and new lab data are returned, you will receive a Clinical Update, indicating the results of your proposed action and whether the animal has responded to your treatment.

Remember…

Your DIAGNOSTIC PLAN should first address the “high yield” problems and primary DfDx’s.

Accordingly, your diagnostic plan may be used to:

- Verify that a problem exists (e.g. a urinalysis is used to verify that the owner’s observation of red urine represents hematuria)

- Localize a problem to an organ system or site (e.g. hematuria is originating in the bladder rather than the kidney or urethra)

- Identify a disease mechanism (e.g. inflammatory disease vs. neoplasia)

- Rule out specific causes or disease entities (e.g. paired titers to address Ehrlichia infection)

You should address your specific DfDx’s according to priority. Focus initially on the probable (i.e. the primary) DfDx’s versus the possible (i.e. less likely) DfDx’s?

Your THERAPEUTIC PLAN, on the other hand, may be supportive, symptomatic or palliative.

It may also be specific (addressing an underlying cause) once a definitive diagnosis is made.

Official Disclaimer: When you reach your clinical rotations, you will find that clinicians have different ways of “SOAPing” cases. For example, in small animal medicine at WSU, you will be required to SOAP each problem on your Master Problem List separately, while some of the large animal clinicians will ask you to SOAP the entire case. There is also wide variation among clinicians regarding what and how much detail they expect. For the DC’s, we ask that you focus on and SOAP the “high yield” problems.

Do I Lump or Do I Split?

Below are some notes regarding “SOAPs” from the WSU Small Animal Referral service – using a short format.

(Or: How to write a SOAP for the Small Animal Referral Medicine rotation at WSU)

By Dr. Rance Sellon, Associate Professor

WSU Dept. of Veterinary Clinical Sciences

There are 2 SOAPs that you will have to write on the SA referral medicine service: a morning SOAP that is not much more than the TPR for the morning and a quick assessment of the patient’s clinical status, and a more detailed, thought-provoking problem oriented SOAP typically written at the end of the day.

An example of the a.m. SOAP could be as follows:

- SO: Buddy is alert and active and has eaten all of last night’s meal. Urination and defecation are normal.

- A: No change in clinical condition from last night.

- P: Proceed with abdominal ultrasound.

- (TPR would be recorded in the boxes on the SOAP.)

On the referral medicine service, patients are seen with multiple problems. To maximize the learning involved from each case, to insure as much as possible that all a patient’s problems are explained and best of all, to emphasize how a problem-oriented approach to medicine can make complex cases easy (well, easier at least), we emphasize a problem-oriented SOAP rather than a case-based SOAP. The following is an example of what we expect (in terms of the thinking process involved and what might be written) for a problem-oriented SOAP.

An 8 year old FS miniature Schnauzer has been seen for polyuria and polydipsia of 3 weeks duration. On physical examination, there is mild hepatomegaly, and evidence that the dog may have lost weight in spite of a good appetite historically. Abnormalities on a minimum data base (CBC, biochemical profile and URINALYSIS) include neutrophilic leukocytosis (PMN= 17,500/l) thrombocytosis (950,000/l) hyperglycemia (330 mg/dl), increased ALP (5300 IU/l), and glucosuria (4+) and a specific gravity of 1.017.

The problem list in your mind would initially look something like this:

- Polyuria/polydipsia

- Hyperglycemia/glucosuria

- Hepatomegaly

- Increased ALP activity

- Neutrophilic leukocytosis

- Thrombocytosis

- Weight loss

The novice would be dismayed at having to SOAP 7 different problems, but you are on referral medicine, and you DO have the power and requisite tool (i.e your brain) to show a little more sophistication when generating your problem list, and amend it to look like this:

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hepatomegaly

- Increased ALP activity

- Neutrophilic leukocytosis

- Thrombocytosis

You are now set to write your SOAP in a problem oriented fashion. The written part could look something like this:

Problem 1: Diabetes Mellitus

SO: This dog presented for a 3 week history of polyuria and polydipsia, and has evidence of weight loss. The liver is slightly enlarged. On the minimum data base, there was hyperglycemia and glucosuria.

Note: we don’t object to formatting the SO portions together like this since the line between subjective and objective information can sometimes be blurry. We also don’t expect a recapitulation of all the laboratory results- mention the abnormals, and don’t waste time rewriting normal values- we can read the clin path sheet too.

A: Diabetes mellitus is supported by hyperglycemia and glucosuria, and history of PU/PD. Weight loss in the face of a normal appetite is common in dogs with diabetes mellitus, and would best explain weight loss in this dog in the absence of clinical signs localizing to other organs. Low urine s.g is seen with diabetes mellitus secondary to osmotic dieresis. Hepatomegaly is also common in diabetes mellitus, but other causes may need to be considered (see problem 2). The possibility of underlying primary renal insufficiency or other concurrent disease as a cause of PU/PD can not be excluded based on available information, and if present would be expected to cause persistent PU/PD after control of blood glucose is achieved.

P: Initiate insulin therapy with NPH 4 U s.c. q 24hr>

Pursue other causes of PU/PD if signs do not resolve with appropriate therapy and response

Problem 2: Hepatomegaly

SO: See problem 1.

A: Hepatomegaly is commonly caused by:

- Congestion (e.g. right hear failure); no murmur ausculted makes this unlikely

- Steroid influences (endogenous or exogenous)- possible given marked increase in ALP activity (see problem 3)

- Lipid accumulation in hepatocytes – commonly seen in diabetes mellitus

- Infiltrative disease (e.g. neoplasia)- can not exclude based on available information

- Hypertrophy/hyperplasia of resident cell types (e.g. monocyte/macrophage hyperplasia or extramedullary hematopoiesis as may be seen with infectious diseases or anemia) – no evidence of cytopenias or active infection/inflammation based on clinical signs although there is neutrophilic leukocytosis (see problem 4).

P: Low dose dex suppression test to R/O Cushing’s disease

Consider abdominal ultrasound, bile acids and aspiration or biopsy if no evidence of Cushing’s disease

Problem 3: Increased ALP Activity

SO: See problem 1. ALP activity is profoundly increased

A: Sources of clinically important increased ALP activity include:

- Steroid influences- glucocorticoids commonly increases ALP activity to this degree because of induction of the steroid isozyme of ALP

- Cholestatic liver disease- can not be excluded based on available information; however, no evidence of icterus, hyperbilirubinemia/uria as might be expected with cholestatic disease; no evidence of abnormal ALT activity suggesting an absence of hepatocellular injury

- Bone origin- increases in ALP activity from bone are typically mild and are rarely associated with increases of this magnitude

P: Low dose dex suppression test

Problem 4: Nuetrophilic Leukocytosis

SO: See previous problems

A: Neutrophilic leukocytosis is often seen in the setting of

- Inflammation (can be infectious or non-infectious); not well supported by history, physical examination- dog appears clinically well, no signs of pain or swelling, and there is no history of fever

- Stress influences (glucocorticoids); supported by other findings (hepatomegaly, profound increase in ALP activity

P: Low dose dex suppression test

Problem 5: Thrombocytosis

SO: see previous problems

A: differentials for thrombocytosis include

- Cushing’s disease: supported by other problems

- Iron deficiency: not supported by normocytosis, normochromasia on CBC

- Chronic inflammatory disease: not supported by available history, PE and laboratory findings (no hyperglobulinemia, proteinuria, fever or other localizing signs)

- Megakaryocytic neoplasia- uncommon, more likely causes supported by other problems (e.g. Cushing’s disease)

P: r/o Cushing’s- low dose dex suppression

Note that the A (for assessment) of each problem is different, but common threads recur through many of them. The A reflects the integration of available information and puts it into perspective for this patient. The P for each problem can vary a bit too, but again, common threads recur – you are making a mistake if you don’t test this dog for Cushing’s disease. We will typically pay most attention to the A and P portions of the SOAP, for this is where your understanding of the case and the problems will be evident.