War on Drugs…War on (some) Drugs (possessed by certain individuals)

daniela.solano

When I first arrived at this institution, the class sizes and the amount of reading that was assigned did little to concern me. The biggest culture shock was the normalization of drug use. A time before the legalization of cannabis in the state of Washington. I was surrounded by students who spoke of their drug habit with no fear, voicing annoyance that they had to figure out who to get it from, smoking in dorm rooms and right outside of dorm room buildings. Confusion mixed with anger flowed through my mind. I spent all of my youth being conscious of stereotypes and the need to stay clear from the slightest hint of misconduct while still being suspected. Making sure to stay far away from drugs, spending my school years constantly being monitored; banning clothing with too many pockets, limiting backpack and locker usage and being ‘cautioned’ -threatened with sporadic drug dog visits. It felt as if they were sure we would mess up and we always had to prove otherwise.

A constant fear of making a wrong decision that would ruin your life was far from the minds of all these new faces I had encountered in college. In the same months I hear those of a higher social status voice their love of cannabis I hear the tear inducing frustration of a student that spent her youth constantly battling the stigma of her peers. Since she was Mexican and her family had property their success was automatically assumed as having been a result of narcotic involvement. The stereotype that racial minorities are the root of our drug problem is something that is still being believed as we have noted with uproar of candidate approval to a certain individual. This fear no matter how misinformed is the voice that is being heard creating an enforcement of policies reflective of the misinformed belief.

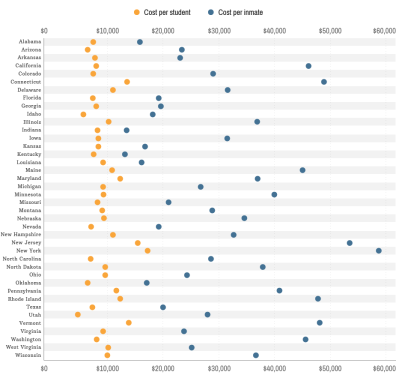

The early seventies proclaimed drug abuse public enemy number one. Giving birth to the War on Drugs and thus enhancing law enforcement and judicial practices. It has cost one trillion dollars after millions of arrest and has resulted in no changes to illegal drug use. Instead we have 500,000 people incarcerated for nonviolent drug crimes. This call for action against drugs have resulted in hyperactive policing of poor persons and minorities even though drug usage is similar across the board and federal studies show more drug use among white youths. Disproportionate arrests that have created horrifying circumstances where white Americans, the majority of this country use crack cocaine more than African Americans but African Americans account for 85% of crack cocaine arrests. A new focus point since the 90s being the arrest of easily targeted poor whites for use of methamphetamine. Not a war on drugs but a war on poverty as displayed by glorified drug arrests.

Early 2000s we have “Pot Princess” Julia Diaco from New York who after multiple drug sales to an undercover narcotics officer facing up to 25 years in prison was sentenced to 5 years on probation. An injustice heightened in this article http://www.drugpolicy.org/news/2006/03/nyu-pot-princess-sentenced-treatment-and-probation-despite-multiple-drug-sales at the comparison of Ashley O’Donoghue, a black man who was also arrested as a first time nonviolent drug offender who is serving seven to twenty one years. Now nearing the end of 2015 we have Sarah Furay an “adorable drug kingpin” of Texas http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/12/01/when-white-girls-deal-drugs-they-walk.html the daughter of a DEA agent possessing five different narcotics along with packing materials and two digital scales.

After learning about the woman from Texas, her privilege and her narcotic possessions, justice would be that she would get served the life ending consequences that come to racial minorities and those living in poverty. But her arrest does little to the fact that the war on drugs has created a target of brown and black bodies and those who live in poor neighborhoods as the worst and ONLY enemy. These stereotypes have created hyper action to one that grant invisibility to another. So long as we keep drug users and dealers in our minds to a certain stereotype we keep the Sarah Furays of this country profitable in their markets and safe from incarceration and public scrutiny. If this policy were really about protecting our children by confiscating drugs that can hurt them, there would be a lot more drug raids on and around college campuses. Furthermore if the war on drugs is truly about keeping people safe which can be interpreted as keeping people healthy we should address the root of why people are seeking narcotics.

References

Giordani, E. (2015). Criminal Justice. In Latino stats: American Hispanics by the numbers. New York, New York: The New Press.

Haglage, A. (2015, December 1). When Whtie Girls Deal Drugs, They Walk. Retrieved December 17, 2015, from http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/12/01/when-white-girls-deal-drugs-they-walk.html

Jarecki, E. (Director). (2013). The House I Live In [Motion picture on DVD]. Virgil Films.

Mohamed, A., & Fritsvold, E. (2012). Dorm room dealers: Drugs and the privileges of race and class (Paperback ed.). Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

Newman, T. (2006, March 22). NYU “Pot Princess” Sentenced to Treatment and Probation Despite Multiple Drug Sales. Retrieved December 17, 2015, from http://www.drugpolicy.org/news/2006/03/nyu-pot-princess-sentenced-treatment-and-probation-despite-multiple-drug-sales

“Supply Demand” Graphic. Mike Keefe. (2009).The Denver Post. www.eaglecartoons.com http://www.ldjackson.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/illegal-drug-demand.jpg

“War on Drugs Message” Graphic. Kirk. Kanderson@pioneerpress.com http://greenwellness.org/wp-content/uploads/war_on_drugs_is_bw_kirk_anderson_20.jpg